October 2, 2025

What is ChatGPT doing?

ChatGPT has opened up a cosmos of creativity.

Six months ago, I set out with a vision to build a couple apps, and maybe even launch them on the App Store. My dream was to build the products I wanted to use day-to-day but couldn’t find in the marketplace. Now — for some important context — I am not a programmer. I’ve dabbled in programming courses over the last couple of years and enjoyed them, but haven’t developed deep fluency.

But then comes ChatGPT, and in less than two months, I built a personal website, launched an app on the app store (GO/DEEPER), and am working on my next technical project.

Awed at the tool at my disposal — and knowing full well that I would not have these products in my opus so quickly otherwise — I set out to understand what’s actually happening every time I ‘vibe code’ with ChatGPT.

I had a couple grounding questions in mind as I started my research:

- How does ChatGPT ‘understand’ my prompt?

- If I had to deconstruct ChatGPT to its most fundamental parts, what would those be?

- How does ChatGPT generate such powerful, cohesive results?

Here I seek to answer these questions, leaning heavily into Stephen Wolfram’s ‘What is ChatGPT Doing … And Why Does it Work?’, as well as Andrej Karpathy’s deep dive into LLMs, and 3Blue1Brown’s incredible videos on neural networks.

In Part 1 and 2, we’ll dig into the fundamentals and more technical aspects of how ChatGPT works (note I have aimed to keep this as non-technical as possible!).

Specifically, in Part 1, we’ll review: how our ChatGPT prompt gets converted into something we can input into the neural network; the architecture of a neural network and what’s happening at each neuron; the importance of ‘weights’ and how weights are adjusted to get better results; and an overview of the pre-training neural networks go through.

In Part 2, we’ll do a deeper dive into ‘Transformers’, given this was a key transformation in neural network architecture (no pun intended) to achieve better, more cohesive results.

Last, in Part 3, we’ll synthesize all we’ve just learned.

Note the essay centers mainly on GPT-3 and GPT-3.5 (the model behind ChatGPT). This essay does not go into reasoning models.

Let’s begin!

PART 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS

A. What are we actually ‘inputting’ into ChatGPT?

When chatting with ChatGPT, it can often feel like it’s really ‘understanding’ our language. But it’s important to remember that ChatGPT’s underlying GPT models understand numbers, not words.

This is because digital computers are number machines, with every operation inside a CPU or GPU—whether adding, multiplying, moving data in memory—happening in bits and bytes, i.e. numbers. And also, because there is no “native” notion of the word “dog” or the letter “A” at the hardware level—only sequences of zeros and ones.

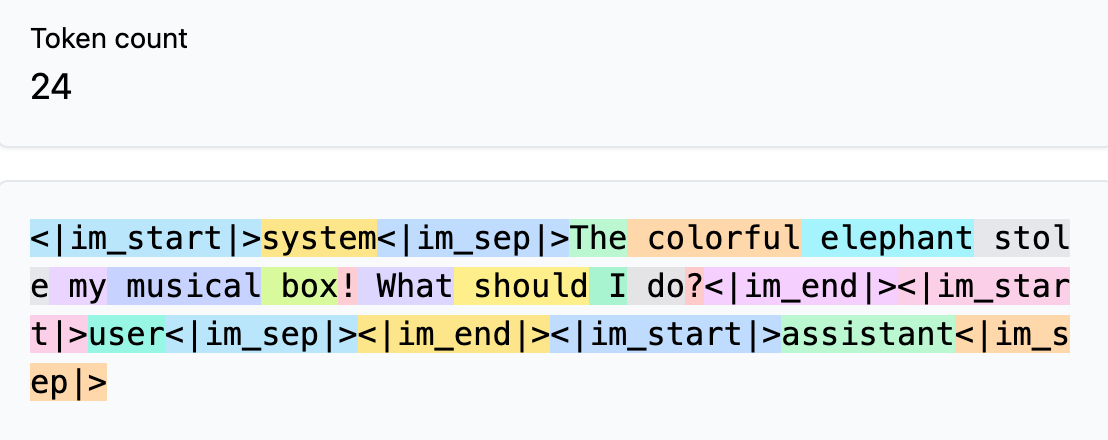

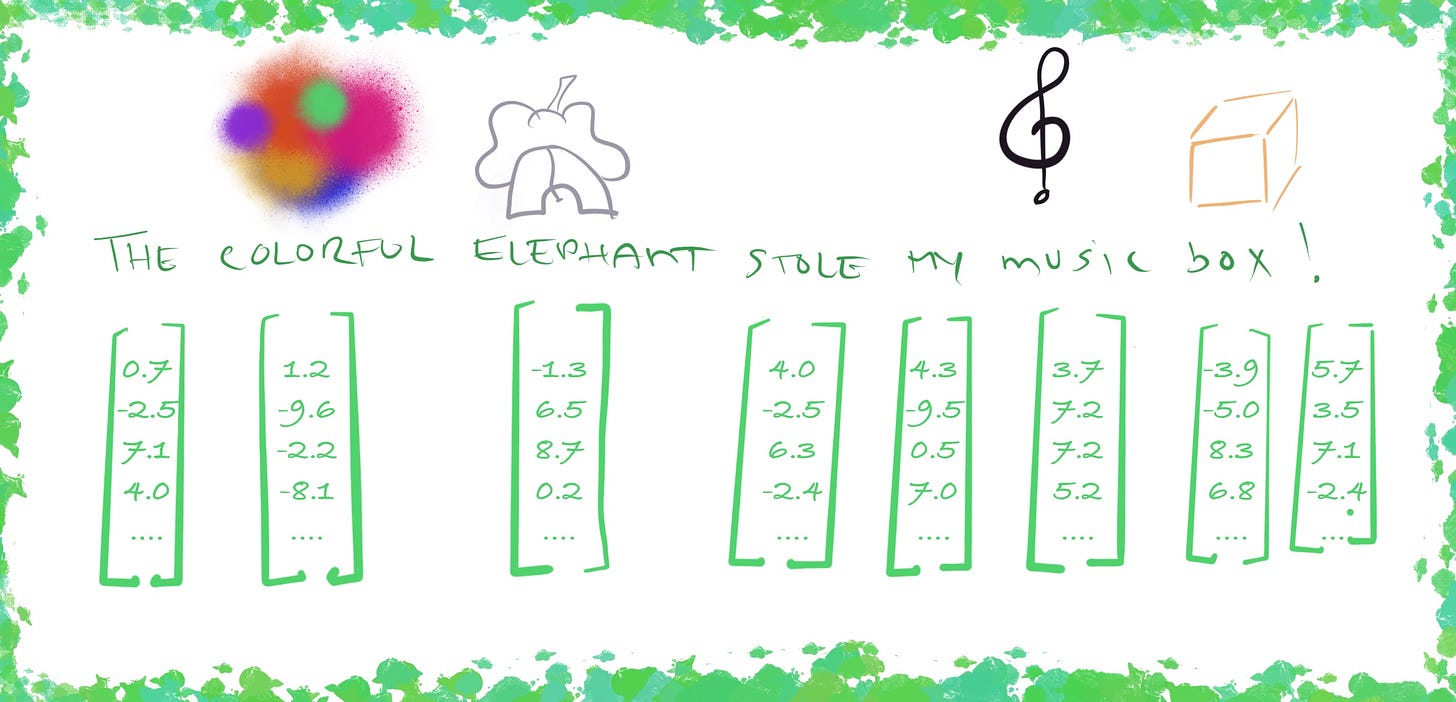

So what happens when you input a text prompt like: ‘The colorful elephant stole my music box! What should I do?’

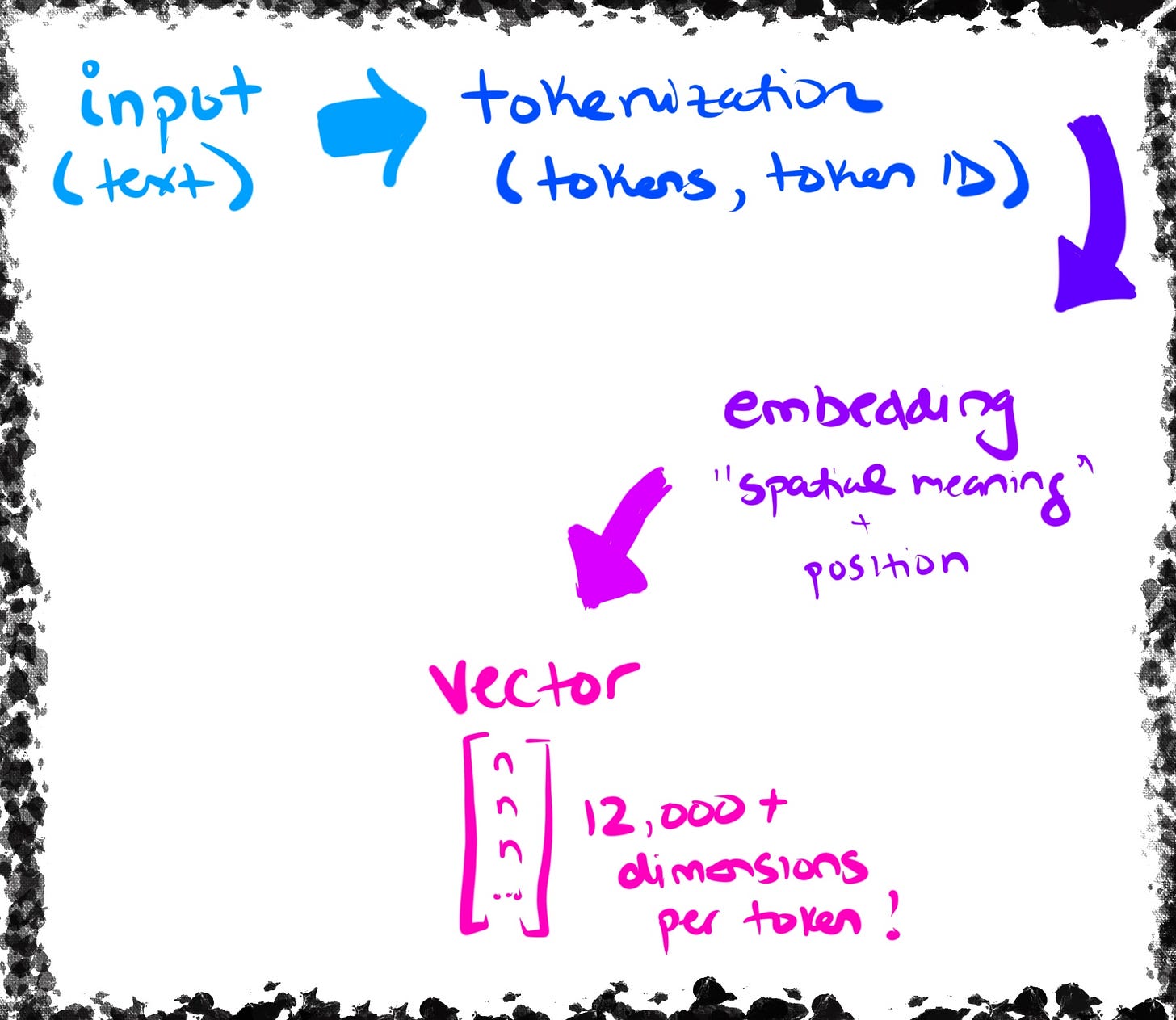

ChatGPT converts each component of your prompt to a token. Tokens can be thought of as individual words, sub-words (like prefixes or suffixes), or characters.

Looking at our example, these are the tokens:

Source: https://tiktokenizer.vercel.app/

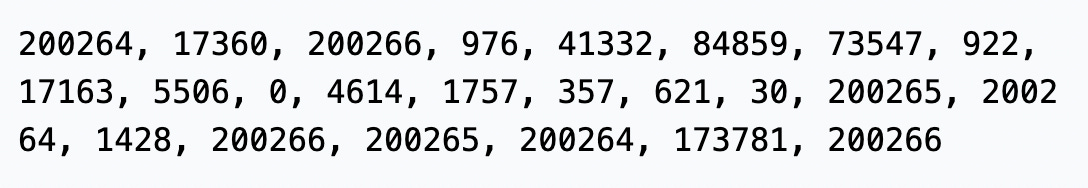

Once ChatGPT has converted our ‘words’ into ‘tokens’, each token is then converted to its integer ID by looking it up in a fixed vocabulary that was learned during model training.

So for example, the token for ‘the’ is mapped to ‘976’, and ‘ elephant’ to ‘84859’.

Source: https://tiktokenizer.vercel.app/

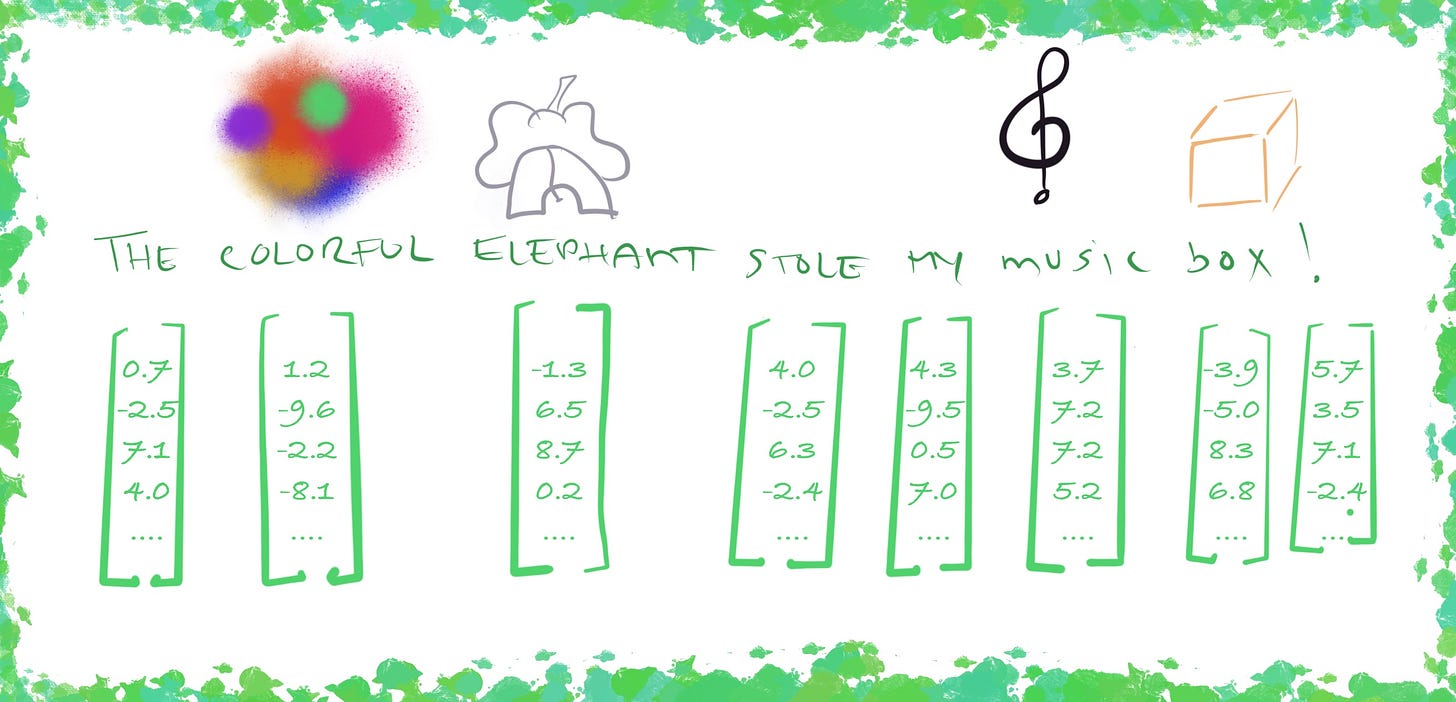

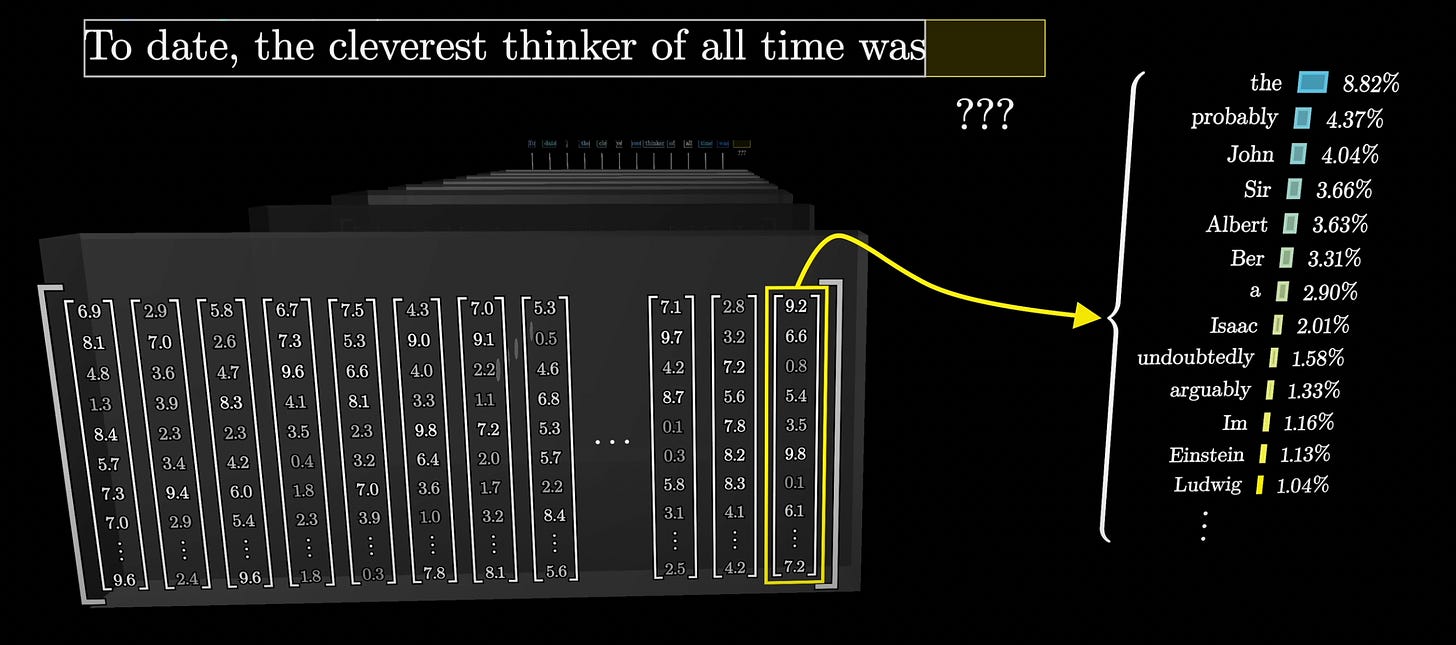

Each token ID then indexes a row in a large embedding matrix, which returns a vector.

You can think of an embedding as a way to represent the “essence” of something via an array of numbers (i.e., a vector) - with each number representing a feature or attribute of the data. The key idea is that embeddings carry a ‘spatial meaning’ to them, whereby nearby things are represented by nearby numbers.

ChatGPT uses over 12K dimensions in each vector (this is mind blowing, given most of us are used to 2D and 3D spaces!).

Here’s a representation of our example, with each token having it’s mapped embedding vector:

Token vector representation.

Let’s use an analogy to help us understand this:

Imagine you’re trying to create the ultimate dating profile. You’d ask each user a handful of questions (i.e., “What’s your love language?”, “Favorite cuisine?”, etc.). Now scale that to 12,000 questions — so everything from your music taste in the 2000s, to your exact preference for coffee roast, to your biggest fear!

Your vector is that enormous questionnaire, with each answer being one number (dimension). You can then imagine that if you’d map out all your users, you’d expect to see two people (let’s call them Romeo and Juliette) whose 12,000 answers align closely to be clustered together (they are a great match!) and further away from people whose answers align ‘less’ with theirs.

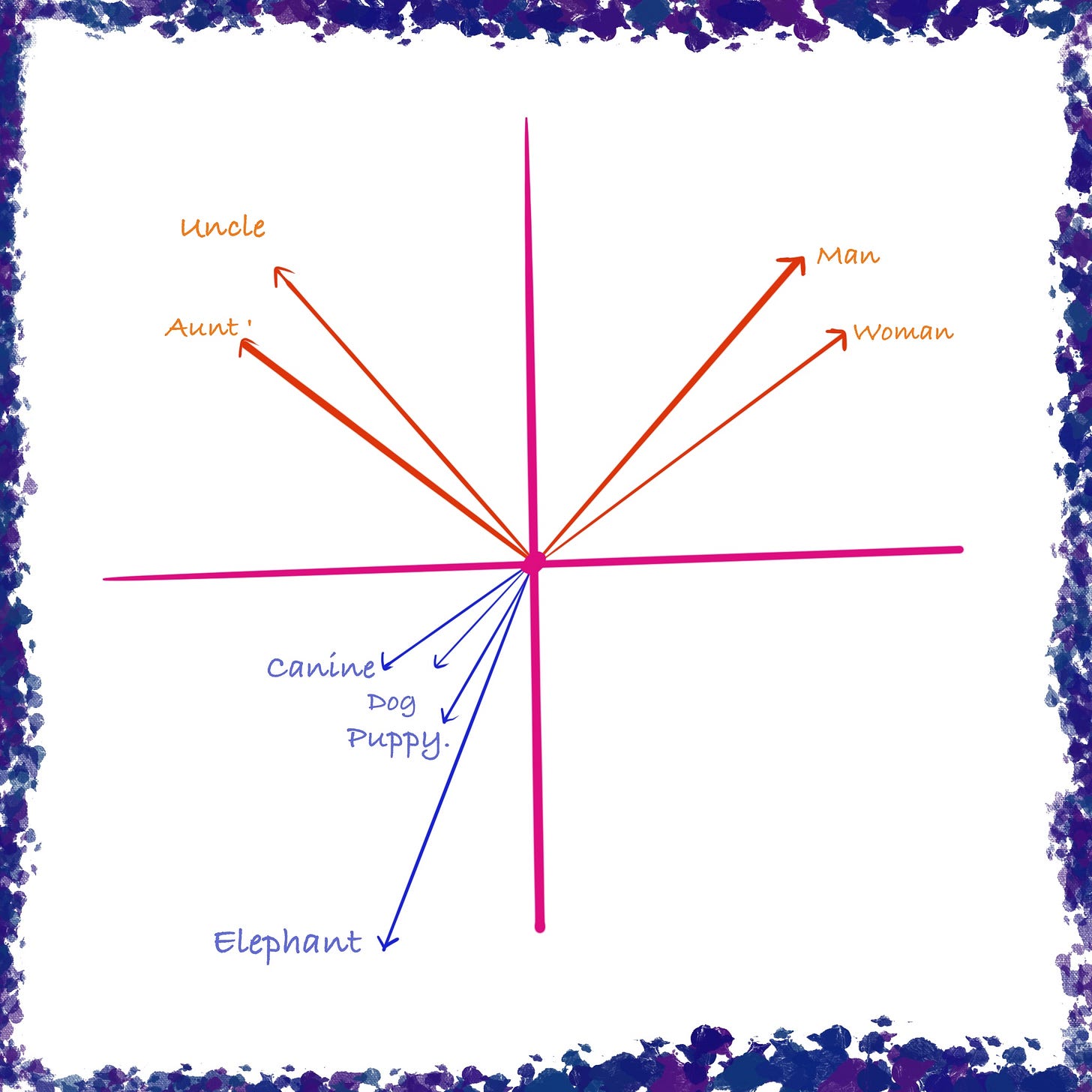

Bringing this back to tokens, this means that tokens with similar embeddings end up closer to each other. So the embedding vectors for ‘dog’ ,‘puppy’, and ‘canine’ will be closer together in space than to ‘elephant‘, for example.

Embedding space (shown here as 2D, but this in actuality is over 12,000 dimensions!)

So how do we go from from token to embedding?

An embedding model is itself a neural network trained to take in tokens and turn them into vectors that capture meaning. When a token enters the model, it first gets represented as a unique ID number (like a dictionary index). That number then passes through layers of the neural network, where each layer transforms it slightly—some layers highlight grammar, others highlight associations, others capture broader themes. During training, the model sees billions of word sequences and adjusts its internal “weights” so that tokens that appear in similar contexts end up with similar vector representations.

You can think of it like putting a word through a series of filters in a photo editing app: the raw word (just an ID number) goes in, and each filter adds more depth—color correction, sharpness, shadows—until what comes out is a rich, detailed image. For embeddings, the output is not a picture but a vector: a set of hundreds or thousands of numbers that place the word on a kind of “semantic map.” On this map, “Paris” ends up near “London,” and math with vectors can even capture analogies like king – man + woman ≈ queen. In this way, the embedding model turns simple tokens into coordinates in meaning-space that the larger language model can use to generate fluent and contextually accurate responses.

So putting it all together, you now have a collection of vectors from your input that ChatGPT can use.

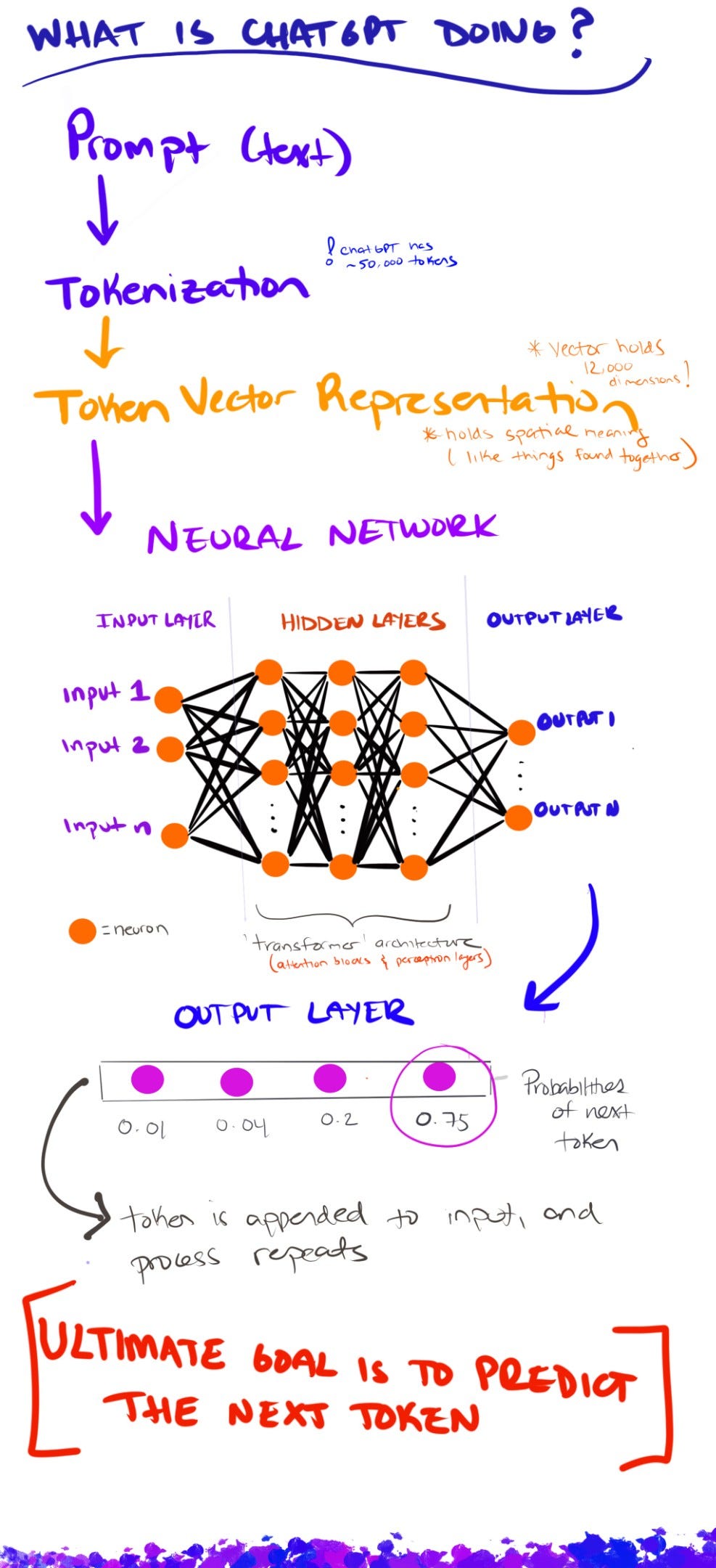

B.We have our vectors — so what happens next inside the ‘neural network’?

First, let’s start with the architecture of a neural network.

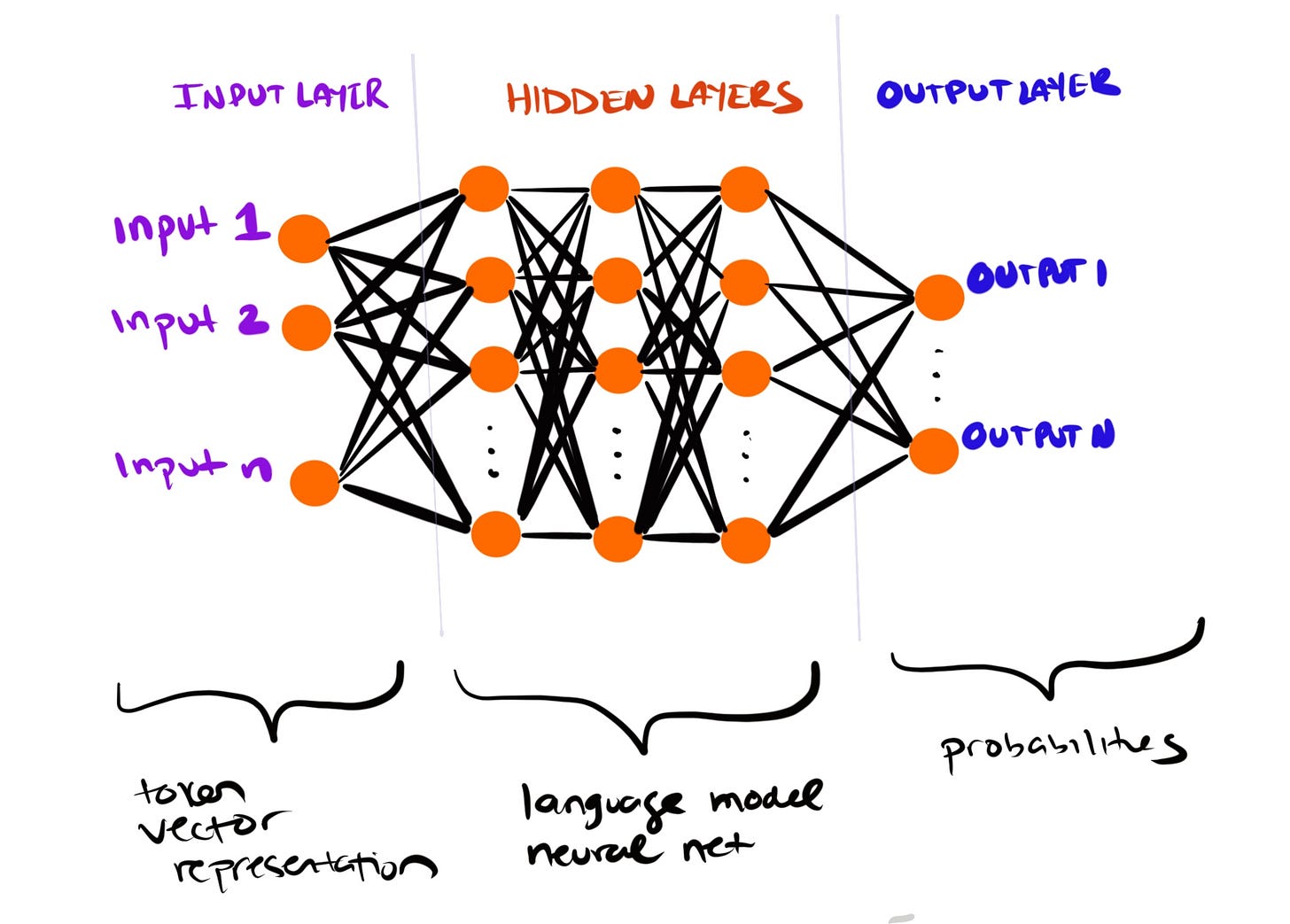

The big picture is that a neural network like ChatGPT is composed of ~100 of consecutive layers made up of ‘neurons’.

Each neuron is set up to perform a numerical function, once it receives an ‘impulse’ from a neuron in the previous layer. Then its result is fed to the neurons in the next layer, and so forth.

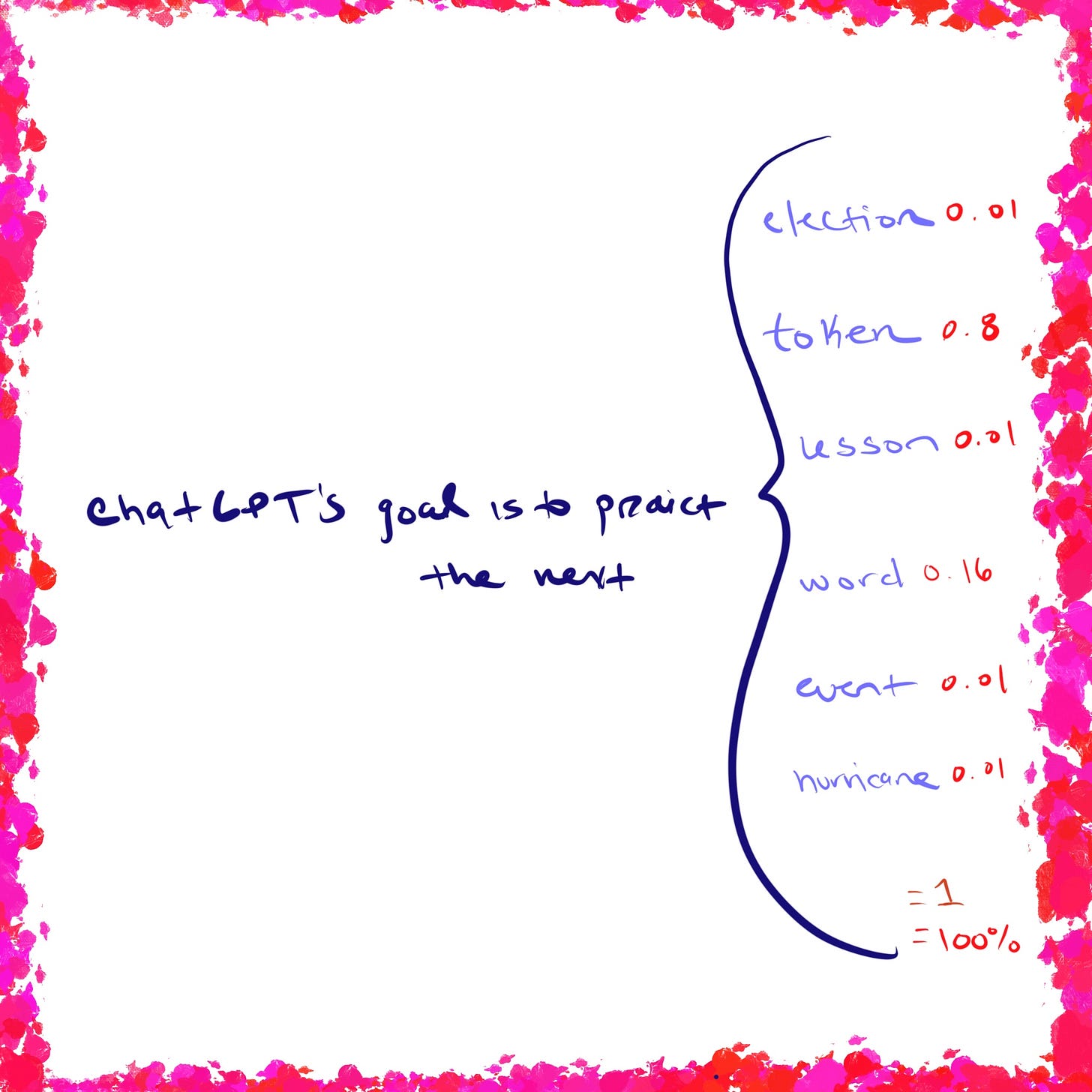

Now, a key concept to remember: probability plays a huge role in shaping ChatGPT’s responses, because the model predicts words by calculating their likelihood from patterns in training data. The final layer of the neural network—called the output layer—produces a probability distribution over the entire token vocabulary (around 50,000 tokens). Each token is assigned a probability score, and the higher the score, the more likely that token is to be selected as the next piece of text.

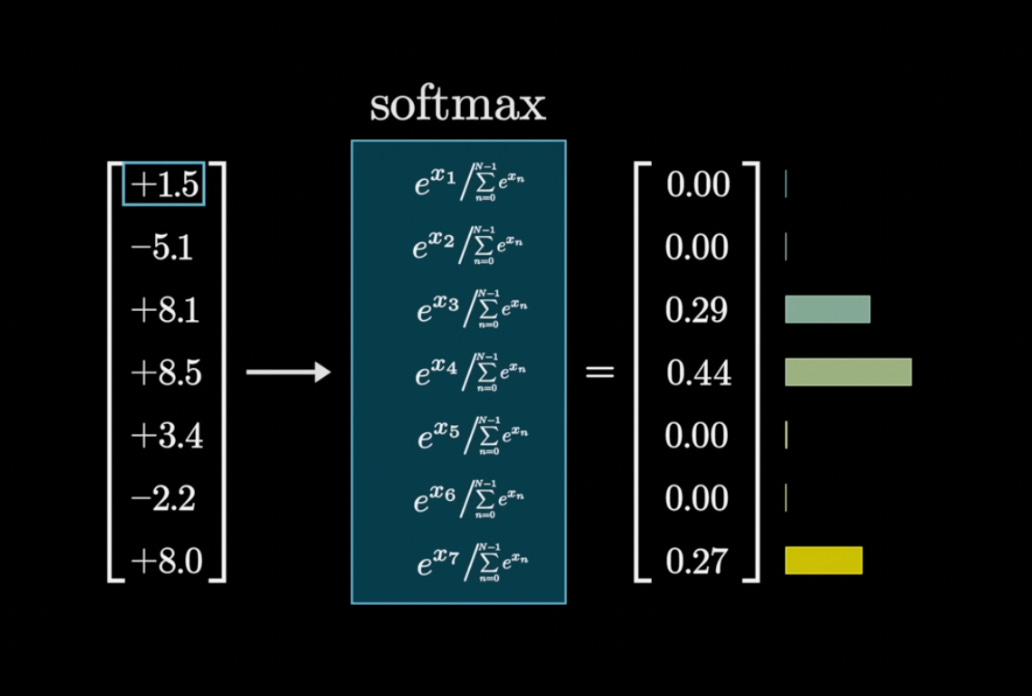

To get slightly more technical, we get the probabilities by performing a softmax function to the last hidden layer (i.e., the last layer before the output layer). The softmax function takes a bunch of raw numbers (which could be positive or negative and on very different scales) and turns them into probabilities that all add up to 1.

Source: 3blue1brown

It’s worth mentioning that ChatGPT will not always ‘choose’ the highest probability token as this would generate a pretty stale, uncreative answer.

Instead, a temperature is set that allows for some randomness in its choice. So perhaps the next token isn’t the highest probability token, but rather the third highest, and so forth.

A neural network with a temperature of 0 has no randomness, and one with a temperature > 1 has a lot of randomness with a flatter distribution of probabilities. Experts have found that the temperature sweet spot is 0.8 (Wolfram).

Now, let’s zoom in a little more — what’s happening in each neuron?

Each neuron takes the outputs from the previous layer, multiplies them by weights, adds a bias, and then applies an activation function.

The weights are important — they decide how much each input matters and represent the strength of connections between neurons. You can think of them as tuning knobs, whereby different tasks we want the neural network to perform are assigned different weights. For every task the network learns, it adjusts these weights to get better at making the right prediction (more on this below!).

Here’s what happens at each neuron:

- First, the neuron calculates a weighted sum of its inputs and adds a bias:

- z = wx + b

- where wx = w1\*x1 + w2\*x2 + ... + wn\*xn

- Next, it applies an activation function — like ReLU — to this value:

- a = f(z)\`

- This output a is then passed to the next layer of neurons, and the whole process repeats.

How are weights adjusted?

Weights are initially assigned random values and then adjusted during the training process.

The goal of adjusting weights is to minimize the error between the network's predictions (i.e., output) and the actual expected or desired outputs for each task. Essentially, weights are the parameters we can tweak to get different, better results in our output layer.

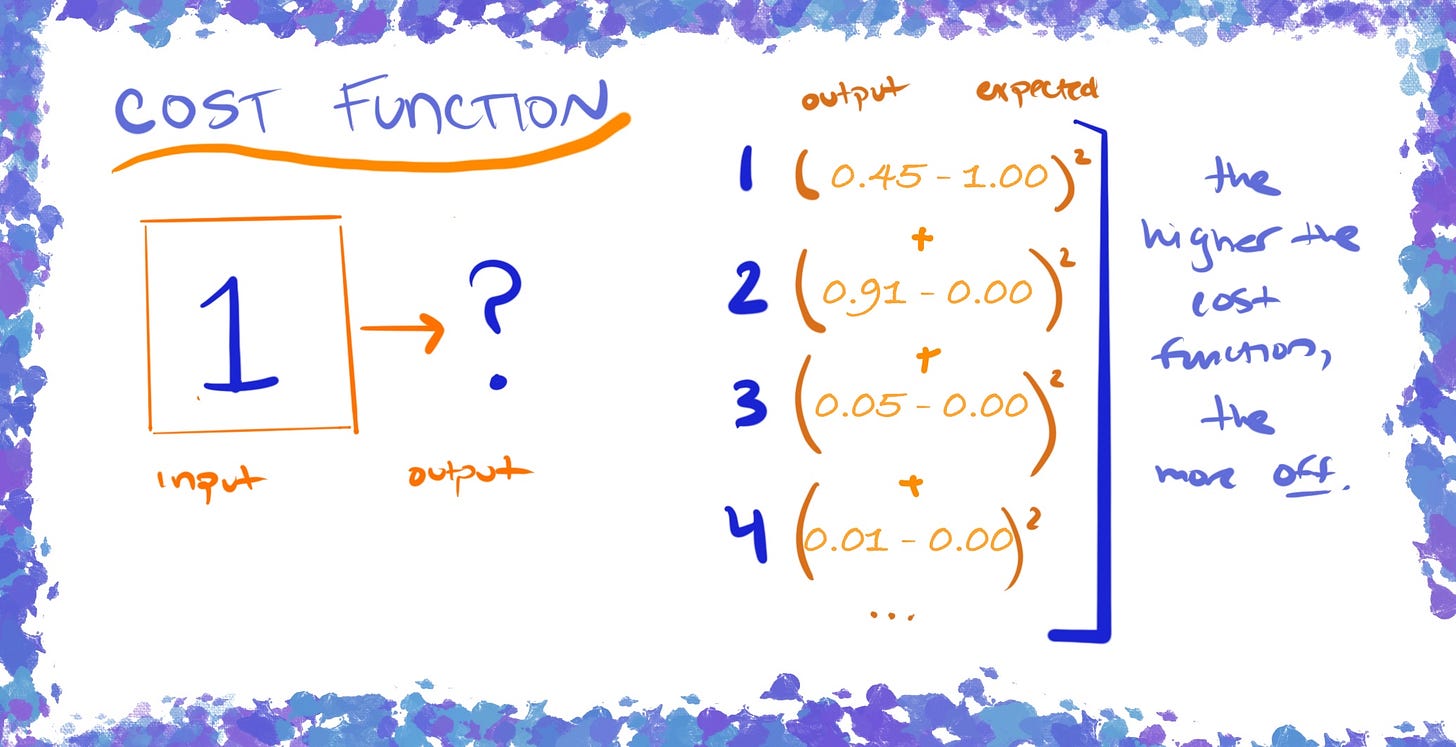

This is done by calculating the Cost Function (also known as Loss Function), which quantifies the error in the model's performance, providing a single number representing the overall "cost" of the model's predictions.

The higher the cost number, the ‘more off’ the model was, and the lower the cost number, the closer to the correct solution. So the goal is to minimize this cost function to improve the model's accuracy.

To get the ‘Cost’, we take sum of the the squares of the difference between the model’s output and the expected output.

Back propagation and gradient descent are then used to progressively find weights that minimize the loss (there’s a lot more math here, but for the purposes of this essay, that’s what we need to know).

Example of how a cost function takes the difference in the expected result (in this case ’1’) to the model’s output.

Ultimately, fine-tuning the model to have the weights that lead to the lowest cost function is what allows us to rely on the neural net post-training to interpolate or generalize between the examples in ‘reasonable’ ways.

Now, let’s take a step back — a neural network is only as good as its training, so I’d be remiss not to give a high-level overview of this.

Before a large language model can be released into the world, it must go through a lot of training. There are three core ways that the neural nets are trained:

The first is Pre-training. The model “reads” (self-supervises on) a huge, diverse text corpus (e.g. web pages, books, code). The objective here is for the model to build general language ability and be able to reasonably predict the next token given previous context. The outcome of pre-training is that the model learns grammar, facts, and broad patterns of language.

Next, there’s Supervised Fine-Tuning. In this training stage, human annotators craft example prompts with ideal responses. The model is thus trained via ‘supervised’ learning on how to respond in ways that mimic the human created ideal responses, and adopts its ‘assistant’ personality.

Last, in Reinforcement Learning, the model generates multiple candidate outputs for various prompts, which human labelers then rank or score from best to worst. To scale this and not have to rely solely on human labelers, a separate ‘reward’ model is trained in parallel to predict the human scores (learning from the trained data of the human labeler’s rankings). The main model is then fine-tuned to maximize the learned reward. The effect of Reinforcement Learning is that the model refines its reasoning, preferences, and response style to align better with human judgments.

(For a deep dive on neural network trainings, watch Andrej Karpathy’s Deep Dive into LLMs.)

PART 2: GENERATING A COHESIVE RESPONSE

We’ve covered how ChatGPT converts our text to vectors, and how the neural network architecture takes these vectors to generate a list of probabilities against what token comes next. But how does ChatGPT give such cohesive answers?

Let’s look at the lexicology of GPT: “Generative Pre-trained Transformer”.

- ‘Generative’: The ability for the neural network to generate the ‘next’ text (really token!)

- ‘Pre-trained’: Nodding to the LLM receiving training before use

- ‘Transformer’: ?

The ‘Transformer’ is arguably the most notable feature of GPT-3 networks and what’s ultimately responsible for the cohesive responses we’re seeing from ChatGPT.

A transformer is a specific kind of of neural network architecture, whose aim is to progressively update the vector embeddings so that they don’t just encode the ‘meaning space’ of a single word, but rather update each token’s embedding to encodes not only its own meaning but also how it relates to—and depends on—every other token in the sequence.

A key component is that it introduces ‘attention’, and the idea of paying attention more to some parts of the sequence than to others.

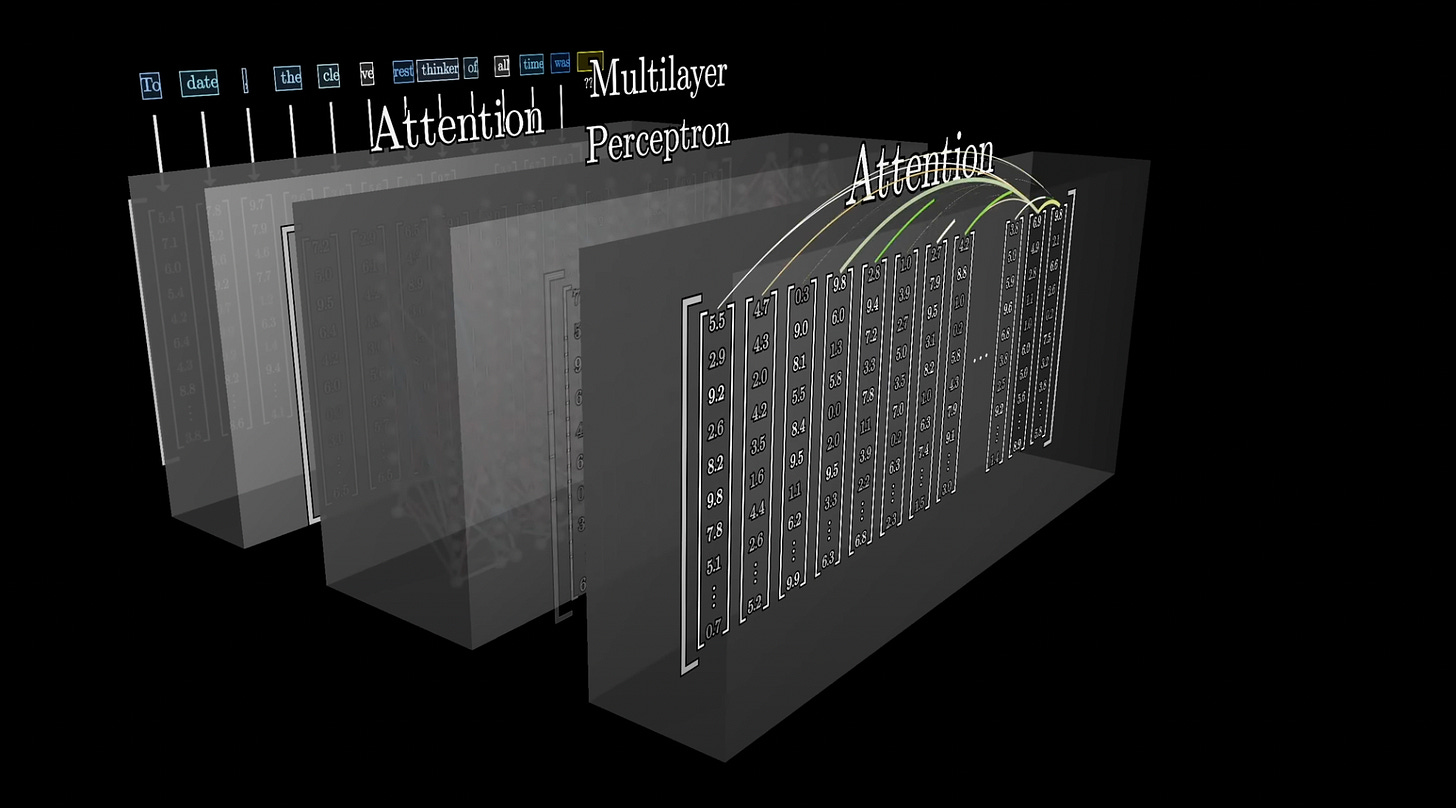

As we learned before, vectors get passed through a series of layers in the neural network. But these layers are not created equal. What’s actually happening is that the vectors get passed through a series of alternating layers of ‘attention’ blocks and ‘multilayer perceptrons.’

*Source: 3blue1brown * Attention blocks are responsible for which words are relevant to updating the meaning of which other words and how those meanings should be updated. You can think of the attention blocks as the ‘communication’ stage of the transformer (Andrej Karpathy).

The key takeaway here is that the vectors are ‘talking to each other’ during the attention block stages. Mathematically, this means there is matrix multiplication happening across vectors, allowing the vectors to ‘exchange’ data.

This is different to what’s occurring within the multilayer perceptron layers, for example, where vectors are not ‘exchanging’ data between each other but rather updating within themselves.

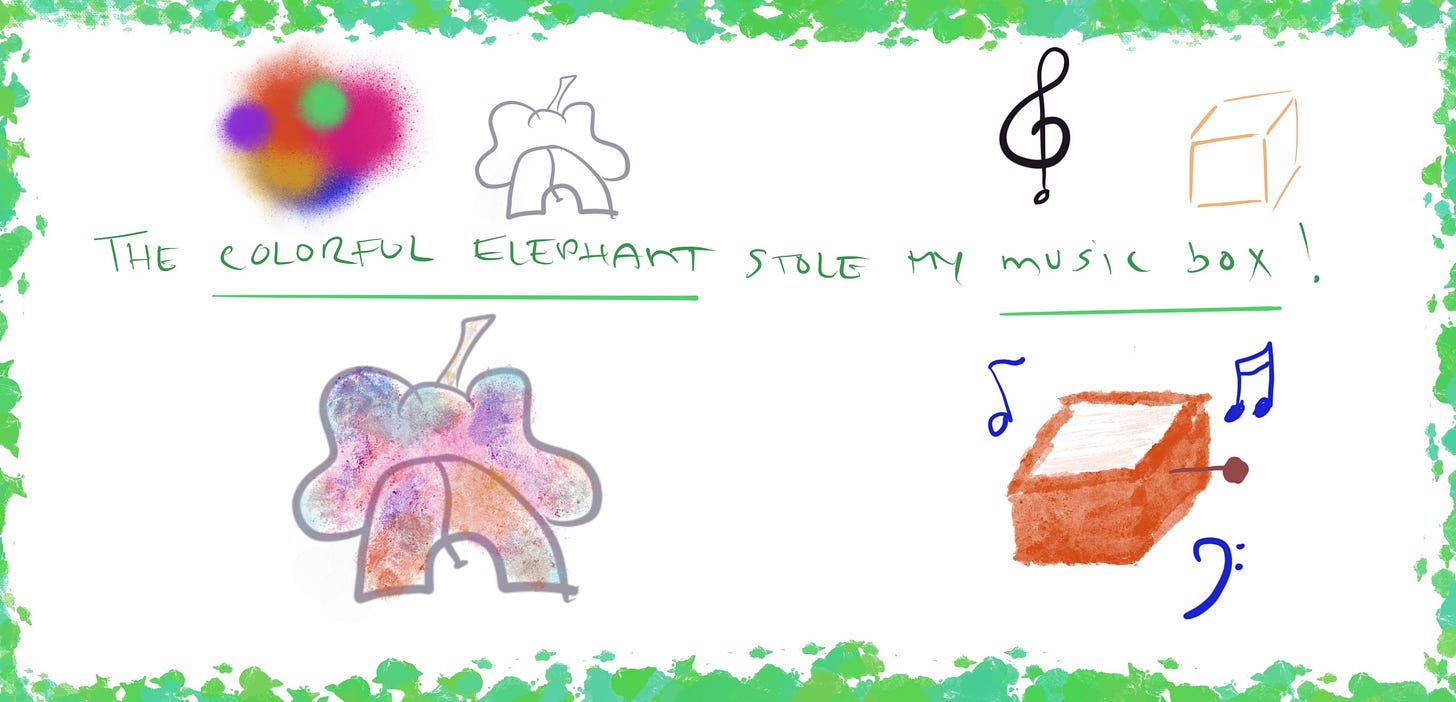

Let’s return to our concept of embeddings. Before the vectors have gone through the attention blocks, you can think of each vector carrying a meaning in a spatial context.

So we could have “The colorful elephant”, whereby “colorful” (based on its vector) would be located in one area of the spatial context, and “elephant” would exist in another. You can think of this as two separate images unrelated to each other— a mix of colors and an elephant.

When the vectors go through the attention blocks, the spatial context changes so that we now have ‘colorful’ influencing ‘elephant’, and now we can think of an image of a ‘colorful elephant’.

The spatial position of this output is different than the original starting points as through the attention blocks, the vectors captured more of the contextual ‘meaning’ of the sentence.

As such, a well trained attention block calculates what it needs to add to the generic embedding (i.e., elephant) to move it to the more appropriate, specific context (i.e., colorful elephant).

You can also think of examples where a noun may have several meanings, such as with ‘wave’ — are we talking about the water movement, the hand gesture, or the energy form?

The starting vector is the same for all examples, but through the attention blocks, the vector for ‘wave’ will ‘interact’ with the surrounding words to then ‘move’ the vector to where it’s most fitting to capture the essence of the word within the correct context. So something like “the news crackled to life over the radio waves’ will end up in a different spatial location than “she surfed that wave”.

Let’s get a little more technical.

Within attention blocks, a series of matrix calculations are performed. This looks something like…

- Each token embedding is projected into three spaces—Query, Key, and Value.

- Query (Q): “What am I looking for?”: Each token projects its embedding into a query vector that represents what it wants to attend to. For example, if the token is a noun, it may be looking for adjectives (“Where are the adjectives?”)

- Key (K): “What do I offer?”: Each token projects into a key vector that represents its own content. For example, if a token is an adjective, it may say “I am an adjective!”

- Value (V): “Here’s my content”: Each token’s value vector is what gets mixed into other tokens’ representations, weighted by how well their Query matches the token’s Key. You can think of Value what actually gets passed along once you’ve decided (via Query and Key) how much to listen to each token.

- The dot product of every Query with every Key produces an attention weights matrix (the higher the score, the more ‘connected’ the tokens are)

- This attention weights matrix is used to compute a weighted sum of the Value vectors.

- That sum is how tokens “talk” and share context.

This process repeats several times, going back and forth between Attention Blocks and Multilayer Perceptron blocks.

The goal is that at the end, the essential meaning of the passage/prompt has been captured in the last vector in the sequence. Then, as discussed previously, we apply the softmax function to get the probabilities of what token should come next.

Source: 3blue1brown

Part 3: RECAP

That was a lot of detail! Let’s synthesize what we just learned.

- **ChatGPT’s ultimate goal is to PREDICT what comes next.** As such, probability plays a big role in the process!

- Before ChatGPT can predict anything, it learns its **internal ‘rules’ by being trained on an enormous text dataset**.

- During training, the **model repeatedly guesses the next ‘word’ (it’s really ‘token’)**, checks if it was right, and adjusts its internal parameters to become better at guessing.

- There is also **fine-tuning with human feedback** whereby humans rate its answers. The model uses that feedback to learn what a ‘good’ answer looks like—making ChatGPT more helpful and more ‘assistant like’ in its responses, and less likely to produce unwanted content.

- ChatGPT’s ‘language’ is not our ‘human’ text, but rather ‘**tokens**’ — which you can think of as characters, words, pre-fixes — that get ‘tokenized’ into numbers.

- These numbers are then **mapped to vectors that carry a spatial meaning**, with ‘like things’ being closer to each other.

- Billions of calculations are then performed with these vectors in the ‘neural net’, which consists of **layers of ‘neurons’** connected to and influenced by each other by different **weights**.

- The most notable features of ChatGPT is a piece of neural net architecture called a ‘**Transformer**’, which introduces the idea of ‘**paying attention**’ to some parts of the sequence more than others. Instead of processing words strictly left-to-right, the Transformer gives each new token a chance to ‘look’ at all earlier tokens, weigh how important each one is, and build a new representation that captures context.

- The last layer of the neural network is **an output with a probability mapped to each token** in CharGPT’s vocabulary — meaning, what token should come next.

- The **‘next token’ is then appended to the input** and the neural net calculation runs again to predict the next token (this is one reason why computing costs are so high!)

- ChatGPT stops generating more tokens for its response when it emits a special “end‐of‐sequence” token, or when it reaches a preset length limits (e.g., “stop after 1,000 tokens”).

And Voila!

If you’ve made it this far, I hope ChatGPT no longer feels like a magical black box to you. Instead, I hope this has given you a platform from which to understand what’s going on behind the scenes each time you prompt ChatGPT, and better yet, inspired your curiosity to learn more.